Jungle of the Warrior Women

Authors note: This was published in an American adventure magazine in 1995.

When the Portuguese first entered the Amazon area, they named it Amazonas, river of the women warriors, because of the natives they encountered. With long hair, clad only in short, plaited palm skirts, and heavily armed with bows, spears and blowpipes, the Portuguese believed them to be women who had cut off their breasts! I was hoping not to meet such fearsome creatures on my trek up the Amazon.

Amongst a small group of Danes, Americans and Australians, I was setting out on a tour to fulfill a dream, exploring the Amazon jungle. Using taxis, boats and buses we arrived at Manacapuru to buy supplies for a three-day tour. After this, it was to be one final hour-long boat ride to our guide’s reserve on a tributary of the river Solimoes.

Upon stepping onto the boat, ‘Jungle Gerry’, our guide, pointed out a grey dolphin cruising up the river. We set off elated, for the dolphins are rare and believed by the natives to be a good omen. Along the way we passed stilted houses fighting a 10-metre annual tidal movement, white egrets and kingfishers, and farms with goats, horses and cattle eking out an existence by the riverside.

Gerry’s 9.5 kilometers square of riverfront land was backed by pure virgin forest owned by the government. He had built a comfortable hut for sleeping, joined to a second hut for the kitchen, dining and siesta area. Both were on stilts above the water to discourage jungle animals and insects, and equipped with a dock for the speedboat and canoes. The last being most important to row to the toilet!

Our welcome drink was a ‘caipirinha’, the local fire water mixed with sugar, lime juice and ice. The first taste was wicked, but it became easier to drink as lunch progressed. After the heat of the journey it was time for a siesta in the hammocks, cooled by a gentle breeze coming through the open windows.

As we were drifting off to sleep, Gerry told us of a story of his youth. He had come across a giant anaconda, 9.2 metres in length. However it was the girth of the beast that surprised him. The bulge in the middle of the snake revealed two whole wild boar in its belly!! When he added that caimans (crocodiles) grew to 7 metres in length a few of us found it difficult to snooze.

We awoke to a beautiful sunset with the jungle symphony coming to life as monkeys, frogs, birds, beetles and other insects arose after the heat of the day. As we sat ready for dinner, Gerry began to tell us about the Amazon region. Scientists say that the river begins in the Huancayo region of Peru, but Jacques Cousteau believes its origins are further south, nearer to Lake Titicaca. Cousteau also believes the Amazon to be 2.5 miles longer than the Nile.

In the wet season 70% of the Amazon jungle is flooded, and 38% normally. The flooded jungle, or ‘Igapo’ as the Indians call it, produces 15-33% of the worlds oxygen supply, depending on low or high water. The remainder of our oxygen is produced by photo plankton in the oceans, which is being depleted by the diminishing ozone layer. The tree leaves in this oily, humus-stained water stay green, even when submerged.

The highland jungle is 85-93% humid all year round, and is constantly renewed by termites eating softwood and lianas killing off the trees or vice-versa. Thus there is a rich layer of humus, 10-15 cm’s deep for half of the year until it is washed away by the big rains.

That night we were lucky enough to go to a once-a -year jungle party. There we saw traditional dances with a strong Portuguese flavour. Young boys and girls dance the story of the coffee barons and the harvest. The girls wear heavy, red velvet dresses and shake baskets of coffee beans. The boys shake their machetes to the same rhythm, dressed in crisp black and white. Unfortunately the full dance, including machete throwing, could not be performed as the roof was too low!

That night we were lucky enough to go to a once-a -year jungle party. There we saw traditional dances with a strong Portuguese flavour. Young boys and girls dance the story of the coffee barons and the harvest. The girls wear heavy, red velvet dresses and shake baskets of coffee beans. The boys shake their machetes to the same rhythm, dressed in crisp black and white. Unfortunately the full dance, including machete throwing, could not be performed as the roof was too low!

As a small child I had read of a spider that ate birds. I asked Gerry about it on the way home that night in the canoe. He told me that the bird-eating spider builds its nest 2 or 3 metres underground, and is the size of your hand or larger. The female kills the male after reproduction and they can jump 2 metres to take birds from their nests. It walks like a crab, and meticulously plucks the feathers from its prey before devouring it. More good bedtime stories!

The next morning we went for a hike in the jungle so Gerry could explain how the Indians use all the different trees and animals to survive. Along the way we spotted a beautiful yellow and black mockingbird, and blood and meat from a meal in the trees where probably an ocelot had caught something. As we walked deeper into the jungle I noticed that every dangling bush was full of either ants or spiders. Gerry took my mind off this as he pointed out colourful fungus, orchids, and all sorts of trees, all of which have a different use.

The ‘ zarabatanga’, or blowpipe tree, is hollow in the middle and can be straightened in a fire to create a weapon for hunting birds and animals. Different species of trees are used for making bows, arrows, spears, drums, canoes and paddles. The ‘itauba’ tree for canoes is very hard, whilst the ‘paraffin’ tree provides for torches, candles and glue for the canoes.

The ‘sorua’ bubblegum tree is exported for processing, but has a sweet milk you can drink without treatment. The redwood tree or ‘paurosa’, is such a big export earner that the government monopolises the industry. When it is ground down, 5 drops of the oil becomes the basis for one litre of perfume. This strong smelling tree is also used to make guitars and violins.

“Envira” trees have a natural linseed oil to protect it from the humidity. The Indians strip the fibre off the bark then coat it in paraffin to preserve it and use it for their bows and their hammocks. When cut correctly, the “cipaudagna” water rope will release its fresh water to drink.

Over hundreds of years the Indians had discovered raw materials for everything they needed, the jungle providing all. Gerry pointed out yet another spider, this one a baby tarantula with an orange spot on its back This led him to tell us how the Indians use the plants and trees to heal them when they are sick.

The “amapa” tree is the strongest of the medicine tress. Its bark can be scraped off and used to clot blood and disinfect a wound, as demonstrated on my arm, scraped raw from an encounter with a moving bus prior to our tour. The pincers of soldier ants are then used to clamp the wound shut. I declined Gerry’s offer of a demonstration on that one.

The amapa tree is also used to cure snake bites, and whilst malaria is very rare ( the black humus-stained water prevents mosquitoes breeding), the bitter-tasting quinine tree is made into tea when the natives suffer from this disease. The Indians use “bengue balsam” bark, boiled in a pot to ease aching muscles, and even the three-sided razor grass is used to shave their light beards.

Nearing the end of this fascinating insight into the jungle, we arrived at Gerry’s pride and joy- a 500- or 600-year-old giant red mahogany, so sturdy that lianas and termites cannot kill it. They take 100 years just to germinate and are so rare that you are lucky to find one in 50 square kilometres. In five years Gerry has not seen it drop a seed to reproduce.

We paddled through the dense flooded jungle, going quietly so that we did not disturb the monkeys feasting and playing in the trees. That night we were to go caiman spotting and we all looked forward to it.

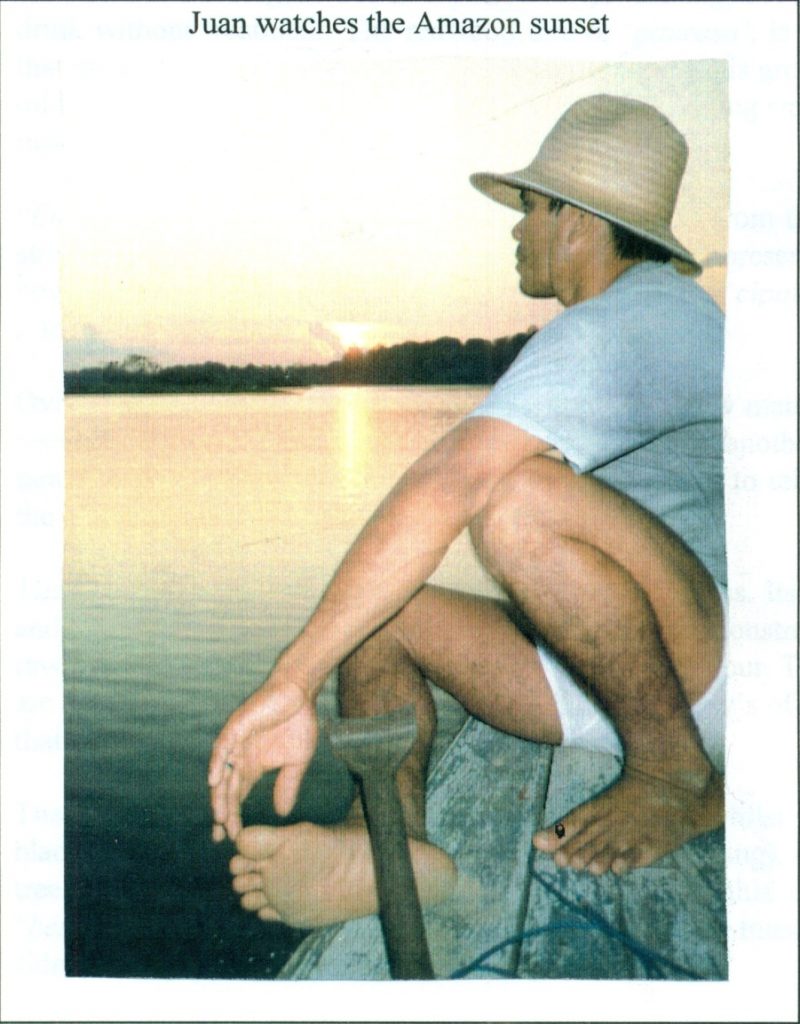

However, it turned out that we were not all going chasing the alligators cousin, only one lucky volunteer. Gerry’s assistant, Juan, and I set off in pitch dark armed with nothing more than a torch. Great! I had visions of monstrous reptiles swamping the boat and devouring me.

As we cruised into the shallows, Juan stuck the torch in his mouth and handed me the paddle, leaving his hands free. By shining the torch in its pink eyes and blinding it, he could then snatch the caiman from the water. We came across one fairly quickly, but I think I spoiled Juan’s aim by rocking the boat as I leaned out to see what was happening. The next attempt was more successful, but I had to laugh with relief when he drew out a foot-long baby, a perfect miniature of the monster I had feared.

Juan took the paddle and handed me the catch while we sped back to camp. I was careful to hold it just behind the head as Juan had shown me, but couldn’t help feeling its soft underbelly and tough armoured back. I did not test its baby sized teeth as it could easily have taken a finger.

When we showed it to Gerry and the rest of the group, he told us the caiman was probably 3 or 4 years old, but could live to 300 and 7metres long. This particular specimen had a piece of tail missing from a piranha bite. The piranhas and caimans naturally keep each other in check. The caiman lays about 30 eggs, and the piranhas make off with 25 When the survivors grow up they feed on piranha. So when there are sufficient numbers of both it is fairly safe to swim. But if hunters kill off too many reptiles the piranha get hungry. Gerry seemed to take delight in these revelations before bedtime.

We set off the next day to try to catch some of these famous Amazon fish for dinner. Gerry showed us how to bait a hook and smash the stick on the water to simulate a fish in distress. Though it was great fun, we were unsuccessful as it was high water and the piranha were scattered. In low water they congregate in the shallows and are easier to catch.

We set off the next day to try to catch some of these famous Amazon fish for dinner. Gerry showed us how to bait a hook and smash the stick on the water to simulate a fish in distress. Though it was great fun, we were unsuccessful as it was high water and the piranha were scattered. In low water they congregate in the shallows and are easier to catch.

Our next stop was a family farm on the river to see how they lived in the jungle. The family it turned out was Juan’s, and they welcomed us as Gerry showed us around. They grow their own coffee, cocoa, mangoes, oranges, bananas, avocados, sugar and spices for cooking, colouring and food preservation. In addition they raise chickens, pigs and goats, keeping dogs, cats, birds, a monkey and a tortoise as pets. The family works as a commune, sharing everything. and working only when they need something: They do not take from the jungle when there is no need. We watched a brother making smooth, hand-crafted canoe paddles, and a sister baking and crushing their own coffee.

Juan’s mother and two other sisters were processing manioc, which is like a swede or potato. It is a poisonous plant, full of cyanide, and has no natural predators. As Juan’s family have been here for over 300 years, they, like the other Indians, have learnt to process manioc in such a way as to render it harmless. A 50 kg bag fetches US $20 in the market, and the by-products are used as chicken feed. The Indians have a monopoly on manioc production for only they know how to process it.

Eight years ago Juan’s family was turned onto the Protestant Assembly of God, who promptly forbade drinking, dancing and some of the local festivals. The missionaries convert the older family members, knowing they will enforce the religion on the whole family. The older children move away when they have their own families, but the younger ones stay at home. We discovered that Juan is the oldest at 33, with a 21 year old wife, and his oldest son is 8 years old. Of his nine brothers and sisters, the youngest is 7. Obviously the new church did not ban everything!!

To finish our trip we went out to the main river to try and spot dolphins coming up the river to feed. Sitting at this unique bar in the middle of the Amazon river, a glass of sangria-like wine in my hand, I was glad I came here. It is truly an amazing place, providing everything for those who live here, one of the last wilderness areas of the world.

To top it all off, we saw an extremely rare sight – a mother and baby of the pink dolphin variety, swimming on the incoming tide. I took this as a good omen for the future of the Amazonas, the river of the warrior women.